Creating basic navigation menus

Summary

In this tutorial we will take you through how to create different types of basic navigation menu using HTML lists and links.

Introduction

In this article you’ll learn about different types of navigation menus and how to create them in HTML. We’ll also touch on the subject of menu usability and accessibility. We won’t go into styling menus yet, but this article will lay the foundations.

the HTML5 <nav> element

HTML5 defines a <nav> element that can be used to contain the primary navigation of a website, be it a list of links or a form element such as a search box. This is a good idea. Previously, we would have contained the navigation block inside something like <div id="navigation">. While this works fine for styling purposes, it is a <div>, and therefore semantically anonymous. The <nav> element provides a consistent way to unambiguously define the primary navigation areas. This is good for both search engine optimization and for visually impaired users. A screen reader user can more easily find the navigation area if it is clearly signposted (this does depend on whether the screen reader supports the <nav> element, so it might be a way off yet). A navigation block would look something like this:

<nav>

<ul>

<li><a href="#">Navigation</a></li>

<li><a href="#">Menu</a></li>

<li><a href="#">Links</a></li>

</ul>

</nav>

Bear in mind that <nav> should only be used for the main navigation elements, not for advertising links at the bottom of the page, or for a secondary navigation relating to a small part of the page.

Your main HTML menu tools: links, anchors and lists

There are several different types of menu and navigation idioms to consider in HTML, all connected closely with <link> and <a> (anchor) elements. In a nutshell:

- Link

<link>elements describe relationships across several documents. You can, for example, tell a user agent that the current document is part of a larger set that spans several documents, including a table of contents, and define the relationships among the documents. - Anchor

<a>elements allow you to either link to another document, resource, or document section, or to a certain section of the current document. These are not automatically followed by the user agent; instead, they’ll be activated by your visitors by whatever means available to them (mouse, keyboard, voice recognition, etc.).

If you haven’t yet read the HTML Links and HTML Lists articles, you should. They contain lots of basic information that will help you understand this tutorial.

Anchors/links do not just become menus on their own; you must structure and style them to let both the browser and your users know that their function is as a navigation menu, not just a set of random links. HTML lists are quite handy for this purpose. If the order of the pages is not important you can use an unordered list. However, if the order in which the visitors go through all the documents is important then you should use an ordered list.

Using <nav> and lists to create menus works well for several reasons:

- It is easy to differentiate the primary navigation lists/links from other lists and links on the page because they are the ones inside the

<nav>. Not only will does this make the navigation meny easier to for screen readers, as mentioned above, but it makes targeting the menu with CSS and JavaScript easier as well. - Lists can be nested, which means you can easily create several levels of navigation hierarchy.

- Even without any styling applied to the list, the browser rendering of the HTML makes sense, and it is easy for a visitor to grasp that these links belong together and make up a logical unit.

You nest lists by embedding the nested list inside the <li> element, not after it. You can see a correct and an incorrect example below.

Notice that browsers display both examples in the same way. Browser display should never be an indicator for the quality of your code. An invalid HTML construct will be hard to style, add behaviour to with JavaScript, or convert to another format. The structure of nested ULs should always be:

<ul>

<li>

<ul>

<li>

</li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>

and never:

<ul>

<li>

</li>

<ul>

<li>

</li>

</ul>

</ul>

The need for flexibility

The menu of a site is unlikely to stay the same for very long — sites tend to grow and change as functionality is added and the user base grows, so you should create menus with scope for menu items to be added and removed as the site progresses, and for menus to be translated into different languages (so links will change in length). Also, you may find yourself working on sites where the HTML for menus is created dynamically using server-side languages rather than with static HTML. This does not, however, mean that knowing HTML will become obsolete; it will actually become more important, as this knowledge will still be needed to create HTML templates for the server-side script to populate.

Types of menus

There are several types of menus you will be called upon to create in HTML as you work on different websites. Most of these can be created with lists, although sometimes interface restrictions force you to use something different (more on that later). The list-based menus you will be likely to create are as follows:

- In-page navigation: For example, a table of contents for a single page, with links pointing to the different sections on the page.

- Site navigation: A navigation bar for your whole website (or a subsection of it), with links pointing to different pages on the same site.

- Content-contextual navigation: A list of links that point to pages closely related to the subject of the page you’re currently on, either on the same site, or on different ones.

- Sitemaps: Large lists of links that point to all the different pages of a website, grouped into related sublists to make them easier to make sense of.

- Pagination: Links pointing to other pages that make up further sections or parts of a whole, along with the current page, for example, part 1, part 2, and part 3 of an article.

In-page navigation (table of contents)

We’ve already covered this to a certain degree in the tutorial about links, but here’s a more in-depth description of what in-page navigation means and what you need to make it work. Each menu link looks like this:

<nav>

<ol>

<li><a href="#intro">Introduction</a></li>

...

The href attribute points to a corresponding anchor (the target)further down the page via the anchor’s id attribute value, preceded by a hash symbol (#). That anchor looks like this:

<h2 id="intro">Introduction</h2>

Each section of the page also has a “Back to menu” link that works in the same way, but points back to the menu instead. Technically, this is all you need to make this kind of navigation work; however, there is an annoying bug in Internet Explorer that forces you do to a bit more work.

You can try out this bug for yourself:

- Open the document in Internet Explorer 6 or 7.

- Do not use a mouse; instead use the keyboard to navigate the document. You can hit the tab key to jump from link to link and the enter key to activate a link — in this case to jump to the section it points to.

- Seemingly all is well when you do that — the browser scrolls down to where you wanted to go.

- If you hit the tab key again the right behaviour for the browser is to take you to (give focus to) the first link inside the section you chose. Internet Explorer, however, will take you back to the start of the menu at the top of the page!

The way around this is terribly confusing and deals with a special property of Internet Explorer called <hasLayout>. You can trigger this in several ways, all of which are explained in Ingo Chao’s article On having layout. The easiest way is to wrap the anchor in an element and then set that element’s width using CSS. In this case we used <section> elements and then set their width to 100% using CSS. This is what IE needs — the anchor must be inside an element with <hasLayout>.

Having to do this is annoying, but it also helps you if you want to style the sections differently — you can’t add styling to a whole section unless you wrap it in an appropriate block level element.

Note that keyboard navigation around links in Opera works slightly differently — try looking at the above example in Opera, then hold down Shift and use the arrow keys to navigate around links (it also works on form elements). This is called spatial navigation.

Site navigation

Site navigation is most probably the most common menu type you’ll need to create. It is a menu of a site or a subset of it, showing both the options visitors can choose from and the hierarchy of the site. Lists are perfect for this purpose.

<nav>

<ul>

<li><strong>Home</strong></li>

<li><a href="about.html">About Us</a></li>

<li><a href="clients.html">Our Clients</a></li>

<li><a href="products.html">Our Products</a></li>

<li><a href="services.html">Our Services</a></li>

<li><a href="contact.html">Contact Us</a></li>

</ul>

</nav>

There aren’t many surprises here, at least not from a pure HTML point of view. In later articles we’ll talk about styling these kind of menus with CSS and adding behaviour via JavaScript. One important thing to consider is how to highlight the current document in the menu, to give the user a sense of being in a particular place, and that they are changing location (even though in reality they aren’t, unless of course they are using a mobile device to browse the Web!). In this case we are just removing the link to the current page — this makes sense, as you don’t need to link to the same document you are on, and it makes it clear where you are in the menu. We’ll look at that next.

Providing visitors with a “You are here” feeling

One golden rule of web development and navigation is that the current document should never link to itself, and its link should be visibly different from the other entries in the menu. This is important as it gives the visitors something to hold on to and tells them where they are on their journey through your site. There are edge cases like web applications, permalinks in blogs, and so-called "one page websites", but in most cases a link to the document you are already viewing is redundant and confusing to the visitor.

In HTML links, we saw that a link is an agreement and a liability: you offer visitors a way to reach more information, but you must be careful — you’ll lose credibility and trust if that link doesn’t give the users what they want, or if it results in unexpected behaviour. If you offer, for example, a link that points to the current document, activating it will reload the document. This is something users don’t expect, and results in confusion and frustration.

This is why the current page should never be linked to from the menu. You could remove it altogether or, even better, highlight it (e.g., by surrounding it with a <strong> element). This gives users a visual clue and also tells vision-impaired visitors that this is something different.

How many options should you give users at one time?

Another issue to consider is how many options to give visitors at once. A lot of menus you see on the web try to make sure that every page in the site can be accessed from one single menu. This is where scripting and CSS trickery comes in — you can make the menu more manageable by hiding certain parts until users select certain areas (rollover menus, as they are sometimes called). This is clever from a technical point of view, but there are several issues with this approach:

- Not all visitors will be able to use the clever trick as intended; keyboard users, for example, will have to tab through all links on the page just to reach the one they are looking for.

- You’ll need to add a lot of redundant HTML to each document of your site to achieve this. If we drill down three levels in a menu to reach the document we want to read, we don’t need to see options leading us to 4, 5, and 6 levels deep.

- You can overwhelm visitors if you present them with too many options at once. It’s easier to make a decision from a short list than a long one.

- If there is not much content on a page but a lot of links, search engines will assume that there is not much valid information on the page and won’t give the page much attention, so it is harder to find when searching the Web.

It is up to you how many items you put into a menu — different designs call for different choices — but if in doubt, you should try cutting your menus down to only the links to the main sections of the site. You can always provide further submenus where appropriate.

Contextual menus

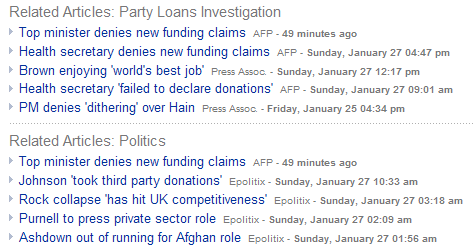

Contextual menus are links that build on the content of the current document and offer more information related to the current page you are on. A classic example is the “Related articles” links you often see at the bottom of news articles, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: An example of a contextual menu in a news article, offering related news items at the bottom.

This is a slightly different thing from context menus in software user interfaces, which offer different options depending on where they are accessed (like the right-click or Ctrl+click menus you find in desktop applications that offer specific options depending on where the mouse pointer is).

Contextual menus on websites are a great way to promote content on other parts of the site; in terms of HTML they are just another list of links.

Sitemaps

Sitemaps are what you might expect: maps of all the different pages of your site (or the main sections of very large sites). They allow your site’s visitors to get a glimpse of the overall structure of your site, and quickly go anywhere they want, even if the page they need is deep within your page hierarchy.

Both sitemaps and site searches are a great way of offering visitors a fallback option when they are lost or to offer quick access for those who are in a hurry. From an HTML point of view they could either be one massive nested list full of links or, in the case of very large sites, section headings with nested links of section-specific hierarchies, or even search forms for each of the sections.

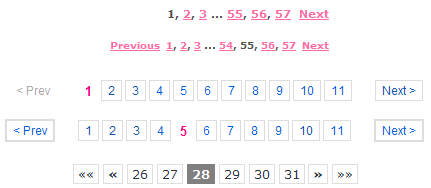

Pagination

Pagination is necessary when you have to offer a way to navigate through large documents split into separate pages. You’ll find pagination in large image archives or search result pages, for example Google or Yahoo search.

Pagination is different from other types of navigation because it does normally link back to the same document, but results in more options or further information being displayed. Some examples of pagination are shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Pagination menus allow visitors to go through large sets of data without losing track of where they are.

The HTML is nothing ground-breaking. Once again, you offer a list of links with the current link (indicating which chunk of data is shown and how far down in the pagination you are) being highlighted (e.g., with a <strong> element) and not linked.

The main difference from site navigation is that there is a lot of programming logic going on with pagination. Depending on where you are in the whole data set you may need to show or hide the previous, next, first, and last links. If you have massive amounts of information to navigate through, you will also want to offer links to landmarks like 0-100 results, 101-200 results, etc. This is why you are not very likely to hard-code menus like these in HTML, but create them on the server-side instead. This does not change the rules, however; the current chunk still should not link to itself, and you shouldn’t offer links that lead nowhere.

When lists are not enough — image maps and forms

In most cases an ordered or unordered list is a sufficient HTML construct for menus, especially as the logical order and nesting also allows for styling with CSS very nicely. There are, however, some situations that may require different design techniques.

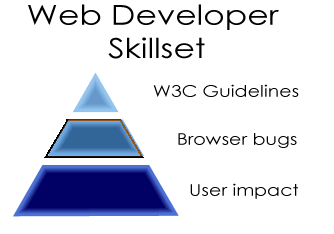

Creating hotspots with image maps

One technique is to use a client-side image map. Image maps turn an image into a menu by turning sections of the images into interactive areas that you can link to different documents. For example, using an image map, a user could navigate by clicking the different sections of the triangle, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: By defining a map with area elements you can turn parts of an image into interactive links.

You can turn any image into a menu by defining a map with different areas (also called hotspots). You give the map a name attribute and connect the image and the map using the usemap attribute on the <img> element. The code in our example looks like this:

<nav>

<img src="skillset.gif" alt="A web developer's skillset - web standards, browser bugs and user impact" usemap="#skillset_Map">

<map name="skillset_Map">

<area shape="poly" alt="W3C Guidelines" coords="90,70,113,112,67,112,90,70" href="w3c.html">

<area shape="poly" alt="Browser Bugs" coords="61,120,115,120,137,157,40,157,62,120" href="browser.html">

<area shape="poly" alt="User Impact" coords="35,166,142,166,171,216,6,216,35,166" href="userimpact.html">

</map>

</nav>

Note that this works exactly like in-page links, which means that you need to precede the value of the usemap attribute with a hash.

Each area has several attributes:

hrefdefines the URL the area should link to (which could also be a target in the same document).altdefines alternative text that can be displayed if the image is not viewable for whatever reason.shapedefines the shape of the area. This can berectfor rectangles,circlefor circles, orpolyfor irregular shapes defined using polygons.coordsdefines the coordinates in the image that should become hotspots. These values are measured from the top left corner of the image, and can be measured in pixels or percentages. For rectangular areas you only need to define the top left and the bottom right corner; for circles you need to define the center of the circle and the radius; for polygons you need to provide a comma-delimited list of all the corner points.

Image maps are not much fun to define and type in as HTML, which is why image manipulation tools like Adobe Image Ready or Fireworks offer an option to create them visually (they generate the HTML for you).

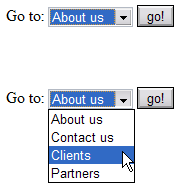

Saving screen space and preventing link overload with forms

Another technique you can employ is to use a form control for navigation. For example, you could use a <select> element, with the different pages as the <option>s. Your visitors can choose an option, then submit the form to jump to different pages.

The most obvious benefit of using this type of menu is that you can offer many options without using much space on the screen, as browsers render the menu as one line as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Select menus take up only one line on the screen.

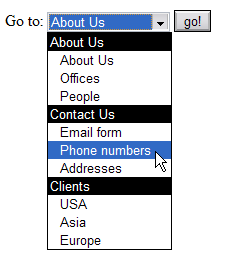

You can go further with this, grouping the different menu options using the <optgroup> element. This will show a menu with non-selectable options (the group names) as shown in Figure 5:

Figure 5: Select menus can use option groups that allow you to tell visitors which options belong together.

This technique has the benefit of using up hardly any space but it also means that you need to have a server-side script to send the visitors to the pages they choose. You can also use JavaScript to make the links work, but you cannot rely on JavaScript being available to all users in all browsers; you must make sure your users can still make use of the menu with JavaScript disabled.

Another, less obvious benefit is that you don’t offer too many links in the same document. This means that you don’t overwhelm users of assistive technologies (who often tend to be presented with the links in one big list). It also means that search engines don’t consider the links on your page worthless as the link-to-text ratio makes the document appear to be a sitemap. However, many assistive technologies can produce a map of your pages’ links; if your important links are all in a select menu, there is a chance that a visitor might never chance upon them. It is therefore a good idea to offer anchor links to the main destination pages and <select> element menus to offer more options. Visitors will be able to use them, but machines like search engine robots don’t need to know they exist.

Where to put the menu, and offering options to skip it

One last thing to mention about HTML menus is that the placement of the menu plays a large role. Consider visitors who have no scrolling mechanism or who might rely on keyboard navigation to find their way around your site. The first thing they’ll encounter when they load the document is its location and the title; next the document gets read top to bottom, stopping at each link to ask the visitor whether they want to follow the link. Other options are to get a list of all the links, or to jump from heading to heading.

If the menu is at the top of document, it will be the first thing the user will encounter, and having to skip through 15 or 20 links before they get to any actual content could be annoying. There are two workarounds available. First, you could put the menu after the main content of the document in the HTML source (you can still place it at the top the screen using CSS if you wish). Second, you could offer a skip link. Skip links are simply links placed before the main menu that link to the start of the content, allowing the visitor to skip over the menu and get to the content immediately. You can add another “Go to menu” link at the end of the document to make it easy to get back up to the top. Skip links are not only useful for users with disabilities, but they make life easier when you navigate a site on a mobile device with a small screen.

Conclusion

There are many ways to construct navigation menus, but no real standards — either official or de facto — for doing so. The best way to see what works and what doesn’t is to visit as many sites as possible and to note, from a user standpoint, how they provide navigation functionality. Then, either emulate menus you like, or strike out and create your own. Your menu design might be the Next Big Thing!

See also

Exercise Questions

- Why is it a good idea to mark up menus as lists?

- When you design a navigation menu, what do you need to plan for in the future?

- What are the benefits of using

<select>elements for menus, and what are the problems? - What do you define with

<area>elements, and what is thenohrefattribute of an area element for (this is not in here, you’d need to do some online research) - What are the benefits of skip links?