Images in HTML

Summary

This article provides an introduction to using images in an HTML document with the <img> tag.

Introduction

In this article we will discuss one of the things that makes web design “pretty” — images. You’ll learn how to add images to web documents in an accessible way so that people with visual impairments can still use the information on your site, how and when to use inline images to deliver information, and how to use background images to improve page layout.

A picture says more than a thousand words — or does it?

It is tempting to use a lot of imagery on your web sites. Images are a great way to set the mood for the visitor, and illustrations help make complex information easier to take in for visual learners.

The drawback of images on the web is that not everybody can see them. Back in the days when images were first supported by browsers, web connections were slow, and you’d pay a lot of money for each minute you were online. Many site visitors had images turned off to save on download costs and get a faster surfing experience. While this is not very common these days, there are still other problems to consider:

- People surfing on mobile devices might still have images turned off due to small screen size or the cost of downloading data.

- Visitors to your site might be visually impaired such that they cannot see your images properly or at all.

- Other visitors might be from a different culture and not understand the icons or diagrams you use.

- Search engines only index text — they don’t analyze images, which means that information stored in images cannot be found and indexed. (At least, not yet: try searching “image indexing” or “search by image” for additional information regarding the latest on image indexing.)

It is therefore very important to choose images wisely and use them appropriately. It is even more important to always offer a fallback for users who cannot see your images. Let’s see what technologies are available to add images to an HTML document.

Content and background images

There are two main ways to add images to a document: content images using the <img> element, and background images applied to elements using CSS. Which method you use depends on your intent:

- If the image is crucial to the content of the document, such as a photo of the author or a data graph, it should be added as an

<img>element with proper alternative text. - If the image is there strictly for aesthetic purposes, you should use a CSS background image. These images should not have any alternative text (what use is the description “round green corner with a twinkle” to a blind person?) and you have more options for image styling in CSS.

The <img> element and its attributes

Adding an image to an HTML document is very easy using the <img> element: you specify the location of the image you want to display as the value of the src (source) attribute, and away you go. The following HTML document displays the photo balconyview.jpg in a browser (provided that the image is in the same folder as the HTML file).

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Example of an inline image</title>

</head>

<body>

<img src="balconyview.jpg">

</body>

</html>

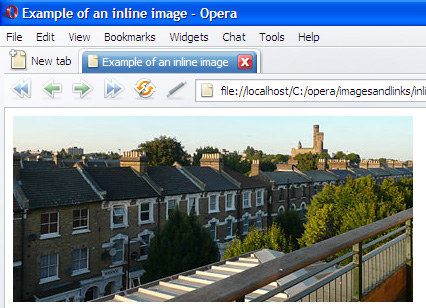

If you run this code in a browser, you’ll get output like this:

Figure 1: The image as it is shown in a browser.

Note: The <img> element is what is known as an empty tag; that is, it does not require an end tag (like </img>). In HTML5, it need not even be closed with an internal slash (like <img src="balconyview.jpg"/>), although many web page authors do so as a matter of consistency.

Providing a text alternative with the alt attribute

Although the image is displayed correctly, the HTML is invalid because the <img> element lacks an alt attribute. This attribute contains text to be displayed if the image is not available for some reason. The image may not be available because it could not be found, failed to load, or because the user agent (normally a browser) does not support images. In addition, people with visual impairments use assistive technologies to read web pages aloud; these technologies look for the contents of the alt attribute to describe the image. It is therefore important to write good alternative text to describe the contents of the image and put it in the image’s alt attribute for reasons of accessibility and search engine optimization.

A quick note: Many web pages — and web authors — use the term "alt tags". This is factually incorrect, as there is no tag (or element) with that name. Remember that alt is an attribute of the <img> element, not a tag.

Thus, in order to make the image understandable for everyone, you must always include proper alternative text, as in this example, "View from my balcony, showing a row of houses, trees and a castle":

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Example of an inline image</title>

</head>

<body>

<img src="balconyview.jpg" alt="View from my balcony, showing a row of houses, trees and a castle">

</body>

</html>

Adding “nice-to-have” information using the title attribute

The alt attribute contains the text that should be displayed when the image is not available. The information in the alt attribute should not be displayed when the image is successfully loaded; Internet Explorer gets this wrong, and shows it as a tooltip when you hover your mouse pointer over the image. Unfortunately, many authors consider this the default, which leads them to put additional information about the image into the alt attribute. Please don’t do this; if you want to add extra information about the image, use the title attribute instead.

Most browsers display the value of an <img> element’s title attribute as a tooltip when you hover your mouse cursor over it (see Figure 2). This can help a visitor learn more about the image, but you cannot rely on every visitor to use a mouse. The title attribute can be very useful, but it is not a foolproof way of providing crucial information. Instead, it offers a good way to provide non-essential information, such as the mood of the image, or what it means in context:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Example of an inline image with alternative text and title</title>

</head>

<body>

<img src="balconyview.jpg" alt="View from my balcony, showing a row of houses, trees and a castle"

title="What I see when I look out of my window; the castle was one reason to move there.">

</body>

</html>

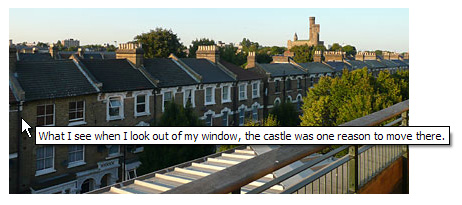

This code will display like this:

Figure 2: title attributes are shown as tool tips in many browsers.

Using longdesc to provide an alternative for complex images

If the image is very complex, such as a chart or diagram, you can offer a more lengthy description of it using the longdesc attribute, so that people using screen readers or browsing with images turned off can still access the information conveyed by the image.

This attribute contains a URL that points to an HTML document containing the same information. For example, if you have a chart showing a set of data, you can link it to a page with the same information using <longdesc>:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Example of an inline image with longdesc</title>

</head>

<body>

<img src="chart.png" width="450" height="150"

alt="Chart showing the fruit consumption amongst under 15 year olds.

Most children ate Pineapples, followed by Pears"

longdesc="fruitconsumption.html">

</body>

</html>

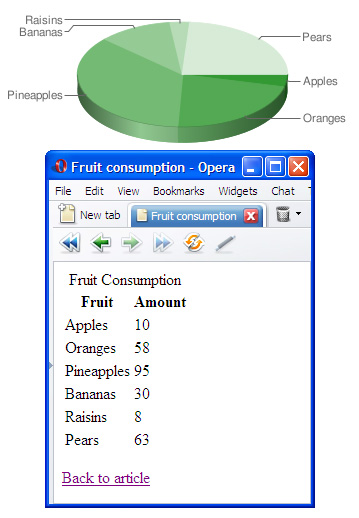

The data file “fruitconsumption.html” contains a table that represents the same data as the chart:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Fruit consumption</title>

</head>

<body>

<table summary="Fruit Consumption of under 15 year olds, March 2007">

<caption>Fruit Consumption</caption>

<thead>

<tr><th scope="col">Fruit</th><th scope="col">Amount</th></tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr><td>Apples</td><td>10</td></tr>

<tr><td>Oranges</td><td>58</td></tr>

<tr><td>Pineapples</td><td>95</td></tr>

<tr><td>Bananas</td><td>30</td></tr>

<tr><td>Raisins</td><td>8</td></tr>

<tr><td>Pears</td><td>63</td></tr>

</tbody>

</table>

<p><a href="inlineimagelongdesc.html">Back to article</a></p>

</body>

</html>

The two different data representations side-by-side look like this:

Figure 3: A document with complex data linked to an image using the longdesc attribute.

Note that there is no visual clue that there is a long description file connected with this image. Most assistive technologies, however, will let their users know there is an alternative available. Some people think that longdesc is pointless, and that you should just provide an alternative page linked via a normal link. This may be appropriate sometimes, as it is often useful to give all users a choice of how they consume your information. There are situations, however, where you’ll want to not show the text link by default.

Faster image display by defining the dimensions using width and height

When the user agent finds an <img> element in the HTML, it starts loading the image the src attribute points to. By default, it doesn’t know the image dimensions, so it will just display all the loaded text lumped together, and then shift it around when the images finally load and appear. This can slow down page loading, and looks unsightly (to say the least) to page visitors. To prevent this, just tell the browser to allocate the right amount of space for the images before they load by providing the image dimensions using the width and height attributes:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Example of an inline image with dimensions</title>

</head>

<body>

<img src="balconyview.jpg" alt="View from my balcony, showing a row of houses, trees and a castle"

width="400" height="186">

</body>

</html>

This will display a placeholder the same size as the image until the image actually loads and takes its place, therefore avoiding the unsightly and unprofessional page shift. Always include the width and height attributes on your images.

You can also resize images using these attributes (try halving the attribute values in the above example), but this is not good practice, as image resizing quality is not smooth in all browsers. It is especially bad to resize images to represent thumbnails, because the idea of thumbnails is to not only have a smaller image in physical size, but also in file size. Nobody wants to load a 300K photo just to see a small image that could have been sent as a 5K file.

Containing images properly using HTML5 <figure>

One problem that has always existed with HTML images is the choice of what container element to put them in. After all, images are inline elements by default: they don’t force line breaks before and after themselves. This is fine for cases where you want to put a small icon next to a piece of text, but you’ll more often want an image to sit on its own line in the page. You could describe this usage as making the image into a separate figure.

In HTML4, the most common way to achieve this is to put the image inside a <p> or <div>, but neither of these is ideal — an image isn’t a paragraph, and a division is semantically ambiguous. Realizing this, the creators of HTML5 introduced a new element that solves the problem: <figure>. This element is specifically designed to contain a figure, which could be an image, two images, or a combination of several multimedia elements, text, or other content. Let’s look at an example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Figure element with figcaption example</title>

<style>

figure,figcaption {

display: block;

}

</style>

<script>

document.createElement('figure');

document.createElement('figcaption');

</script>

</head>

<body>

<figure>

<img src="balconyview.jpg" alt="View from my balcony, showing a row of houses,

trees and a castle" width="400" height="186">

<figcaption>The view from outside my window.</figcaption>

</figure>

</body>

</html>

Proper captions using HTML5 <figcaption>

Another new addition to HTML5 is an element for containing figure captions. Previously this was done using <p> or some other not-wholly-appropriate element, but now we have the <figcaption> element. Nested inside a <figure>, it says “this is the caption to go along with the contents of this figure.” For example:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

...

<figure>

<img src="balconyview.jpg" alt="View from my balcony, showing a row of houses, trees and a castle"

width="400" height="186">

<figcaption>The view from outside my window.</figcaption>

</figure>

...

</html>

Note that the contents of the figure caption do not necessarily act as a replacement for the contents of the alt attribute or the title attribute: it depends on whether the caption accurately describes everything in the image, or provides the same supplementary information that the title attribute does. In this case, we need an alt attribute as well, as sighted users can see what is in the image by looking at it. The alt attribute says exactly what the image contains for the benefit of users who can’t see it, while the caption gives some more context.

Background images with CSS

It is pretty safe to say that web design became a lot more fun when browsers started supporting CSS. Instead of hacking around in the HTML using table cells for positioning items on the page, non-breaking spaces ( ) to force alignment, and spacer GIFs (transparent 1x1 pixel GIF images resized to create margins), we can now use padding, margin, dimensions, and positioning in CSS and leave the HTML free to just worry about the content structure.

CSS also means you can use background images in a very versatile way — you can position them behind and around your text any way you want, and also repeat images in regular patterns to create backgrounds. Before closing, we’ll cover CSS images briefly.

How to apply backgrounds with CSS

The CSS to apply images as backgrounds is fairly straightforward. Before you look at the CSS code below, have a look at this multiple example to get an idea of the different things that are possible with background images in CSS:

Figure 4: Backgrounds with CSS.

The boxes are actually styled <h2> elements with some padding and borders applied with CSS to allow space for the background image. The CSS for the first example is:

background-image:url(ball.gif);

You add the image with the background-image property and give it a URL in parentheses to specify the image to be included. By default, background images are repeated both horizontally and vertically to fill up the whole element space, as in the first example. But you can define various repetition schemes with the background-repeat property:

- Don’t repeat the image at all:

background-repeat:no-repeat; - Only repeat the image horizontally:

background-repeat:repeat-x; - Only repeat the image vertically:

background-repeat:repeat-y;

By default, the background image (if not repeated) will be positioned at the top left corner of the element. You can, however, use background-position to move the background image around. The easiest values to use are top, center, and bottom for vertical alignment, and left, center, and right for horizontal alignment. For example, to position the image on the bottom right, use background-position:right bottom;, while to center the image vertically on the right use background-position:right center;.

By controlling the repetition and the position of background images and using clever images you can create stunning effects that were not possible before CSS, and by keeping the background definitions in a separate CSS file you make it very easy to change the look and feel of a whole site by changing a few lines of code.

Conclusion

HTML images are a powerful and flexible way to provide non-textual information, enhance the value of other content, and improve the visual attractiveness of your pages. Combining tried-and-true techniques with new HTML5 elements and attributes can help ensure that your web pages are useful, interesting, and accessible.

See also

Exercise Questions

- Why is it important to add good text to an image in an

altattribute? Are there any situations in which you don’t need to? - If you have an image that is 1280x786 pixels large and you want to display it as a 40x30 pixel thumbnail, can you do that in HTML and is it wise to do so?

- What does the

longdescattribute do, and how do browsers show it? - What do the

valignand thealignattributes do and why weren’t they covered here? - Where are CSS background images positioned inside an element by default, and how do they get repeated by default?