The purpose of JavaScript

Summary

In this article, we discuss what JavaScript can be used for on the web, its downsides, and how to use it responsibly.

Introduction

Now the Web Standards Curriculum has taken you through the core essential concepts of programming, it is time to take a step back from the details and take a high-level look at what you can actually do with JavaScript — why would you want to take the time to learn such a complicated subject, and use it on your web pages?

This is an interesting time, as the usage of JavaScript has moved away from a fringe knowledge matter to a mainstream web development skill over the last few years. Right now, it is difficult to get a job as a web developer without JavaScript skills.

How people came to like JavaScript

Computers used to be much slower and browsers were bad at interpreting JavaScript. Most developers came from a back-end development world. Back then, JavaScript just seemed like a bad idea.

On the other hand, the cost of hosting files was very high. This is where JavaScript came in: JavaScript is executed on users’ computers when they access the page, meaning that anything you can do in JavaScript will not add processing strain onto your server. Hence, it is client-side. This made sites much more responsive for the end user and less expensive in terms of server traffic.

Skip forward to today – modern browsers have well-implemented JavaScript, computers are much faster, and bandwidth is a lot cheaper, so a lot of the negatives are less critical. However, cutting down on server round-trips by doing things in JavaScript still results in more responsive web applications and a better user experience.

The downside of JavaScript

Even with all these improvements, there is still a catch: JavaScript is flaky. Not the language itself but the environment it is implemented in. You do not know what computer is on the receiving end of your web page, you do not know how busy the computer is with other things, and you do not know if some other JavaScript in another tab of the browser is grinding things down to a halt. Until browsers begin having different processing resources for different tabs and windows (also known as threads), this will always remain an issue. Multiple threading is made available to a certain degree by a new HTML5 feature called Web workers, and this has reasonable browser support.

In addition, JavaScript is frequently turned off in browsers because of security concerns, or because JavaScript is often used to annoy people rather than to improve their experience. For example, a lot of sites still try to pop-up new windows against your wishes, or cover the content with advertising until you click a link to get rid of it.

What JavaScript can do for you

Let’s take a step back and count the merits of JavaScript:

- JavaScript is very easy to implement. All you need to do is put your code in the HTML document and tell the browser that it is JavaScript.

- JavaScript works on web users’ computers — even when they are offline!

- JavaScript allows you to create highly responsive interfaces that improve the user experience and provide dynamic functionality, without having to wait for the server to react and show another page.

- JavaScript can load content into the document if and when the user needs it, without reloading the entire page — this is commonly referred to as Ajax.

- JavaScript can test for what is possible in your browser and react accordingly — this is called Principles of unobtrusive JavaScript or sometimes defensive scripting.

- JavaScript can help fix browser problems or patch holes in browser support — for example fixing CSS layout issues in certain browsers.

That is a lot for a language that until recently was laughed at by programmers favouring “higher programming languages”. One part of the renaissance of JavaScript is that we are building more and more complex web applications these days, and high interactivity either requires Flash (or other plugins) or scripting. JavaScript is arguably the best way to go, as it is a web standard, it is supported natively across browsers (more or less — some things differ across browsers, and these differences are discussed in appropriate places in the articles that follow this one), and it is compatible with other open web standards.

Common uses of JavaScript

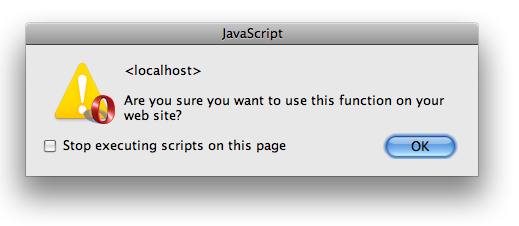

The usage of JavaScript has changed over the years we have been using it. At first, JavaScript interaction with the site was mostly limited to interacting with forms, giving feedback to the user, and detecting when they do certain things. We used alert() to notify the user of something (see Figure 1), confirm() to ask if something is OK to do and either prompt() or a form field to get user input.

Figure 1: Telling the end user about errors using an alert() statement was all we could do in the early days of JavaScript. Neither pretty nor subtle.

This led mostly to validation scripts that stopped the user to send a form to the server when there was a mistake, and simple converters and calculators. In addition, we managed to build highly useless things like prompts asking the user for their name just to print it out immediately afterwards.

Another thing we used was document.write() to add content to the document. We also worked with pop-up windows and frames and lost many a nerve and pulled out hair trying to make them talk to each other. Thinking about most of these technologies should make any developer rock forward and backward and curl up into a fetal position stammering “make them go away”, so let’s not dwell on these things — there are better ways to use JavaScript!

Enter DOM scripting

When browsers started supporting and implementing the Document Object Model (DOM), which allows us to have much richer interaction with web pages, JavaScript started to get more interesting.

The DOM is an object representation of the document. For example, the previous paragraph (check out its source using view source) in DOM-speak is an element node with a nodeName of p. It contains three child nodes:

- a text node containing "When browsers started supporting and implementing the " as its

nodeValue; - an element node with a

nodeNameofa; - another text node with a

nodeValueof ", which allows us to have much richer interaction with web pages, JavaScript started to get more interesting.".

The a child node also has an attribute node called href with a value of "http://www.w3.org/DOM/" and a child node that is a text node with a nodeValue of "Document Object Model(DOM)".

You could also represent this paragraph visually using a tree diagram, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: A visual representation of our sample DOM tree.

In human words, you can say that the DOM explains both the types, the values, and the hierarchy of everything in the document — you do not need to know anything more for now. For more information on the DOM, check out the Traversing the DOM article later in the course.

Using the DOM you can:

- Access any element in the document and manipulate its look, content, and attributes.

- Create new elements and content and apply them to the document when and if they are needed.

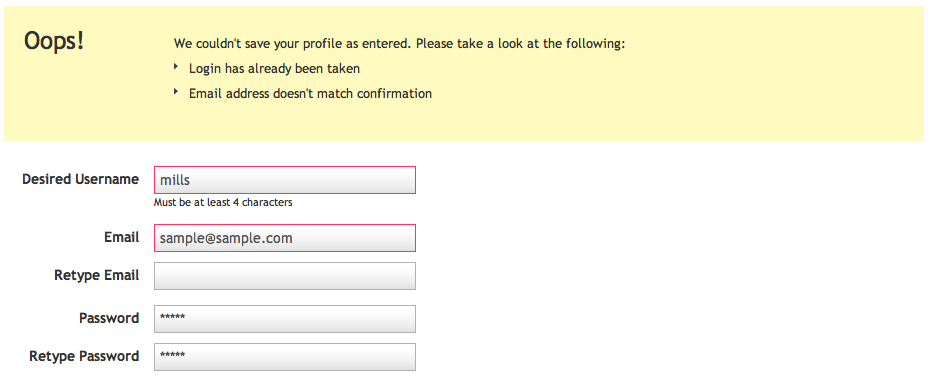

This means that we do not have to rely on windows, frames, forms, and ugly alerts any longer, and can give feedback to the user in the document in a nicely styled manner, as indicated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Using the DOM you can create nicer and less intrusive error messages.

Together with event handling, this is a very powerful arsenal to create interactive and beautiful interfaces.

Event handling means that our code reacts to things that happen in the browser. This could be things that happen automatically — like the page finishing loading — but most of the time we react to what the user did to the browser.

Users might resize the window, scroll the page, press certain keys, or click on links/buttons/elements using the mouse. With event handling, we can wait for these things to happen and tell the web page to respond to these actions as we wish. Whereas in the past, clicking any link would take the site visitor to another document, we can now hijack this functionality and do something else like showing and hiding a panel or taking the information in the link and using it to connect to a web service.

Events are covered in much more detail in the Handling events in JavaScript article later in the course.

Other modern uses of JavaScript

And this is basically what we are doing these days with JavaScript. We enhance the old, tried and true web interface — clicking links, entering information and sending off forms, etc. — to be more responsive to the end user. For example:

- A sign-up form can check if your user name is available when you enter it, preventing you from having to endure a frustrating reload of the page.

- A search box can give you suggested results while you type, based on what has been entered so far (for example “bi” could bring up suggestions to choose from that contain this string, such as “bird”, “big”, and “bicycle”). This usage pattern is called autocomplete.

- Information that changes constantly can be loaded periodically without the need for user interaction, for example sports match results or stock market tickers.

- Information that is a nice-to-have and runs the risk of being redundant to some users can be loaded when and if the user chooses to access it. For example the navigation menu of a site could be 6 links but display links to deeper pages on-demand when the user activates a menu item.

- JavaScript can fix layout issues. Using JavaScript, you can find the position and area of any element on the page, and the dimensions of the browser window. Using this information you can prevent overlapping elements and other such issues. Say for example you have a menu with several levels; by checking that there is space for the sub-menu to appear before showing it, you can prevent scroll-bars or overlapping menu items.

- JavaScript can enhance the interfaces HTML gives us. While it is nice to have a text input box you might want to have a combo box allowing you to choose from a list of preset values or enter your own. Using JavaScript, you can enhance a normal input box to do that.

- You can use JavaScript to animate elements on a page — for example to show and hide information, or highlight specific sections of a page — this can make for a more usable, richer user experience. There is more information on this in the JavaScript animation article later on in the course.

Using JavaScript sensibly and responsibly

There is not much you cannot do with JavaScript — especially when you mix it with other technologies like Canvas or SVG. However, with great power comes great responsibility, and you should always remember the following when using JavaScript:

- JavaScript might not be available — this is easy to test for, so not really a problem. However, things that depend on JavaScript should be created with this in mind, and you should be careful that your site does not break (i.e. essential functionality is not available) if JavaScript is not available.

- If the use of JavaScript does not aid the user in reaching a goal more quickly and efficiently you are probably using it wrong.

- Using JavaScript, we often break conventions that people have got used to over years of using the web (for example, clicking links to go to other pages, or a little basket icon meaning “shopping cart”). Whilst these usage patterns might be outdated and inefficient, changing them still means making users change their ways — and this makes humans feel uneasy. We like being in control and once we understand something, it is hard for us to deal with change. Your JavaScript solutions should feel naturally better than the previous interaction, but not so different that the user cannot relate to it via their previous experience. If you manage to get a site visitor saying “ah ha — this means I do not have to wait” or “Cool — now I do not have to take this extra annoying step” — you have got yourself a great use for JavaScript.

- JavaScript should never be a security measure. If you need to prevent users from accessing data or you are likely to handle sensitive data, then do not rely on JavaScript. Any JavaScript protection can easily be reverse-engineered and overcome, as all the code is available to read on the client machine. Also, users can just turn JavaScript off in their browsers.

Conclusion

JavaScript is a wonderful technology to use on the web. It is not that hard to learn and it is very versatile. It plays nicely with other web technologies — such as HTML and CSS — and can even interact with plugins such as Flash. JavaScript allows us to build highly responsive user interfaces, prevent frustrating page reloads, and even fix support issues for CSS. Using the right browser add-ons (such as Google Gears or Yahoo Browser Plus) you can even use JavaScript to make online systems available offline and sync automatically once the computer goes online.

JavaScript is also not restricted to browsers. The speed and small memory footprint of JavaScript in comparison to other languages brings up more and more uses for it — from automating repetitive tasks in programs like Illustrator, up to using it as a server-side language with a standalone parser. The future is wide open.